Squirrels could contribute to space travel and more, says Montreal researcher

- Mackenzie Sanche

- 10 avr. 2022

- 3 min de lecture

Dernière mise à jour : 10 janv. 2024

Mackenzie Sanche - Monday, April 11, 2022

Squirrels and space might not sound like such a good match after seeing Scrat from Ice Age: Collision Course send an asteroid straight toward Earth, but there is reason to believe squirrels might actually be helpful when it comes to space travel.

Montreal biologist Matthew D. Regan studies how hibernating squirrels maintain their body mass to discover if it could potentially contribute to muscle health in astronauts, as well as aging and food-deprived populations.

Also an assistant professor at the Université de Montréal, Regan studies animal physiology, nurturing his curiosity to understand how animals survive in hostile environments. “Ideally, I wanted to do something that could be beneficial to humans, to people,” he said.

After three years of research and collaboration with experts from different fields, Regan’s study was published in late January 2022. Their goal was to confirm a theory dating back to the 1980s that claimed squirrels’ metabolisms could recycle their body’s protein. Proving this theory right is the first step toward various scientific advancements, which caught the Canadian Space Agency’s (CSA) eye.

How does it work?

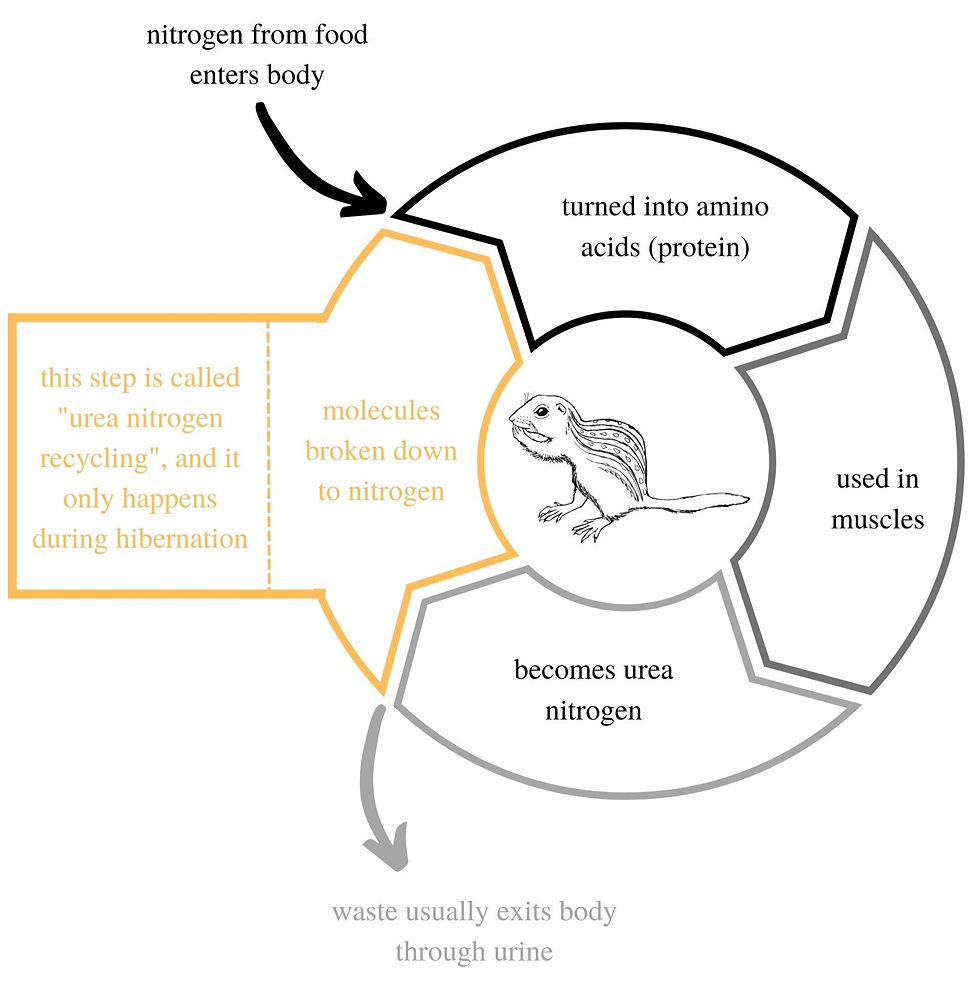

So what can squirrels do that humans don’t? Humans' digestive system is monogastric — their stomachs have only one chamber. When monogastic mammals eat, they absorb nitrogen from their food, which their body turns into amino acids – protein. “Nitrogen is really important because it is the key atomic building block for protein,” explains Regan.

Muscles can then use this protein, converting the nitrogen into urea along the way. Normally, urea exits the body through urine, but hibernating three-lined squirrels do this differently.

Because they do not feed or move much during winter, squirrels should lose muscle mass, but their metabolism allows them to stay strong and healthy. That’s because their gut’s microbiome can break down urea waste and retrieve the nitrogen to make brand new protein molecules for their muscles to use.

Think of it like recycling: instead of losing their nitrogen reserves, they break it down and re-use it. Just like humans make new products out of recycled plastic bottles, for example.

Why choose to study squirrels?

According to Regan, working with animals that have a will of their own is a challenge, but it is much simpler with squirrels than bears, per se. His team decided to study this process with three-lined squirrels, mainly for practical reasons.

The researchers simply moved them into a cold, dark room and waited for September. “They’re pre-programmed to go into hibernation,” says Regan. “And then, you know, it’s like… ‘We’ll see you in six months,’” he laughs, waving.

Another reason for choosing squirrels is that they are monogastric animals, just like humans, meaning they only have one stomach compartment. Regan explains that humans can recycle urea nitrogen, but not to the same extent as hibernating mammals.

“We do have the necessary machinery in place, it just may need to be optimized,” he says, referencing a study from the nineties. He believes they would probably have to create some kind of probiotic pill to enhance our systems.

What’s in it for humans?

Using a mechanism like urea nitrogen salvage can prevent muscle atrophy, the shrinking of the muscles often caused by lack of activity, food, or gravity. If squirrels’ metabolism didn’t allow for this process during hibernation, they would lose all of their muscle mass, complicating their mating season when they wake up.

Because Regan’s study can have big impacts on humans’ quality of life, even the Canadian Space Agency’s curiosity was piqued – enough for them to offer the biologist a $150 000 grant to further his research over the next two years.

While Regan’s study doesn’t mention astronauts at all, he is very passionate about space and was happy when other experts brought it up. Even more so when the CSA showed interest in his study.

According to Nancy Lévesque, a space medicine specialist at the CSA, muscle atrophy during space flight is an important risk to mitigate. Because astronauts’ bodies don’t need to constantly fight gravity, their muscle mass decreases remarkably and maintaining it requires intensive workouts.

Finding a way to reproduce nitrogen recycling in humans would allow astronauts to better maintain their muscle health in space and maybe even allow for longer space missions, says Regan.

Lévesque explains the CSA decided to offer Regan the research grant because this study is beneficial not only for the astronauts' health, but also for the health of those suffering from muscle loss due to aging, osteoporosis, and other important aging-related risks here on Earth.

Regan thinks these discoveries could also benefit people confined to bed rest or induced coma, and even malnourished populations worldwide.

Regan says it’s fun for him to think of his research potentially affecting space flight. Although most benefits are only speculative for now, he strongly believes that, “It’s these earthbound problems that stand to benefit most from this, so that’s probably where we’ll see most effort directed at the beginning.”

I have also created a TikTok style explainer video on this topic.

Commentaires